An interest in foreign affairs sparked alumnus Allan Mustard's interest in foreign languages, leading to a dual major in Slavic Languages and Literatures and Political Science. These degrees, combined with an M.S. in Agricultural Economics, led to a 30-plus-year career in the Foreign Service. Allan describes his career below.

The path from a small dairy farm in western Washington to a 30-plus-year Foreign Service career and seven postings abroad led through the UW Slavic Department. I was introduced to foreign cultures and cuisine at age 5 during a visit aboard the M/V Jaladuta of the Scindia Steam Navigation Company from Bombay, while it was docked in Hoquiam to load logs. This sparked an interest in foreign affairs that twelve years later led to study of the only two foreign languages offered at Grays Harbor College in Aberdeen, Russian and German. That in turn led to a dual major at the UW, in Slavic Languages and Literatures and in Political Science, for Washington at the time had the largest undergraduate program in Russian language in the United States, with over 200 students, as well as one of the best.

Right out of college (which included a summer program in Leningrad, as St. Petersburg was known in Soviet times), I went to work for the U.S. Information Agency as a temporary guide-interpreter on an agricultural exhibit that toured Kishinev (now Chisinau), Moldova; Moscow, then the Soviet capital; and Rostov-on-Don. This job, my first after graduation, lasted for seven months and involved discussing, debating and discoursing on life in America, American foreign and domestic policy, the U.S. economy, race relations, housing, popular music, and even the occasional question about agriculture – all in Russian, of course. In Moscow I met Jim Brow, then an agricultural attaché at the U.S. Embassy, and he encouraged me to consider joining the Foreign Agricultural Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Roughly three years later, with a master’s degree in agricultural economics (from the University of Illinois) under my belt, and following a year with Jewish Family Service in Seattle resettling Soviet émigrés, the Foreign Agricultural Service hired me, and four years after that posted me to Moscow.

That was during the Gorbachev era, and our work included more than the usual crop estimation and negotiation of grain sales. We had a robust exchange program dating to the Nixon-Brezhnev summit in 1972. Russian language skills were paramount as almost nobody in the Soviet agricultural bureaucracy spoke English, and outside Moscow, virtually nobody did. The Soviets restricted our travel, and after a round of spy expulsions in late 1986, harassed us almost constantly. The Soviet government also withdrew our local staff that October, so that American officers had to assume administrative and housekeeping tasks previously handled by Soviet nationals. That’s when the administrative officer discovered I can touch-type in Russian, and arranged for me to be assigned to half-time work in the admin section. That wasn’t half bad – when it was 30 below zero outdoors and others were chipping ice or shoveling snow, I was at least indoors, although around New Years the embassy lost its heat plant till spring.

Even then, however, we could see the cracks in the façade of the Soviet monolith. After a crop trip in Spring 1988 via Kharkov, Kiev, Rostov, Krasnodar, and Mineralnye Vody, my conversations with friends and business contacts, all in Russian, convinced me that the Soviet Union would be doomed when the disillusioned then-30-something generation came to power in another couple of decades. My confidential cable reporting that observation was declassified a few years ago – my insight was correct, but I was off by about a decade and a half, as the USSR collapsed only a little over three years later!

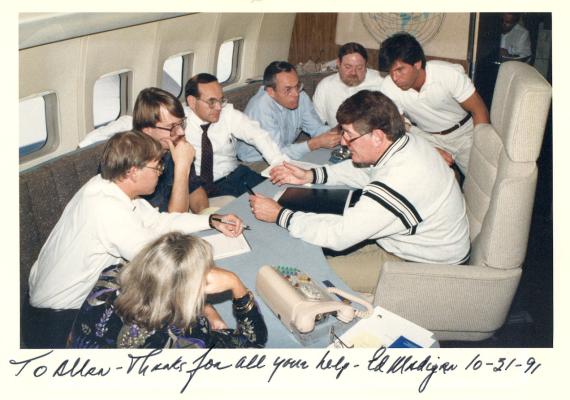

In 1990 headquarters asked me to return from a posting to Istanbul to be what was initially called the “resident Sovietologist” at USDA. President Bush had asked each Cabinet department to form a nerve center to deal with change in the East Bloc, including the USSR, and I was responsible for the Department of Agriculture’s analysis of what was going on, evaluation of the changes, and then recommending policy alternatives. This job quickly evolved into a broader mandate as State Department created an interagency group revolving around the coordinator of assistance to the newly independent states (Ambassador Richard Armitage, and later Ambassador Thomas Simons), following the Soviet Union’s collapse in December 1991. USDA was heavily involved in this effort, for following the August 19-21, 1991, coup attempt against President Gorbachev, President Bush dispatched two USDA missions to the USSR at the request of President Gorbachev to examine the food situation. I planned both missions and accompanied Under Secretary Richard Crowder and a small government-only delegation on the first, in September. Two weeks later, stretching into October, I joined Secretary of Agriculture Edward Madigan and a mixed public- and private-sector delegation of subject matter experts on the second mission, to Moscow and Kiev. These missions and the results of our analysis led ultimately to the largest U.S. foreign food aid program since World War II, as we sought to calm the Soviets and to assure them they would not starve as their world changed dramatically. Over the next five years USDA also implemented technical assistance programs in the former Soviet Union, some of which I conceived and designed, including an effort to promote privatization of Russian grain trade (until then largely a state monopoly).

One other event of that period was the now-forgotten December 1991 airlift by the Department of Defense of surplus B-rations left over from Operation Desert Storm to Moscow and Leningrad, for distribution to orphanages. State Department requested my assistance, for in the words of Gary Grappo, then on the Soviet Desk at State, “We need someone who knows both Russian and food.” My first task was to review the packing list, which I discovered contained freeze-dried foods the Russian orphanage cooks would have no inkling how to prepare. State quickly provided the instructions, and I got on the phone to my old UW grammar instructor Nora Holdsworth, who patiently assisted me in translating the recipes into proper culinary Russian (my knowledge of Russian, though solid, failed when it came to the distinctions among food preparation verbs!) I typed the instructions up and upon arrival in Moscow had the embassy photocopy them for distribution with the goods. My next challenge was to cajole a Soviet Army major in charge of vehicle dispatch at Sheremetyevo Airport to summon trucks for loading from the C-5A transport planes that had flown the B-rations in. He was not terribly pleased with the situation and was ignoring the American transport officer requesting his help. I summoned some vocabulary rarely used by Russian scholars, but which I had learned years before while playing cards with Soviet émigrés, and the trucks began rolling, first to planeside, and then to the orphanages.

After roughly five and a half years shuttling between Washington and Moscow, in 1996 I was posted to Vienna with regional responsibility for seven countries, including five with Slavic languages: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia. I won this posting over 30 other applicants in part because of all of us, I was the only one with facility in at least one Slavic language. After arrival I found that with high fluency in Russian I could muddle through reading newspapers in all of them but Slovene (1000 years of Austrian rule apparently injected so many German words, unrecognizable in their Slovene versions, that I could not puzzle that language out). I could also speak pidgin Serbo-Croatian, enough to get directions when lost, to ask for help, and in one instance to obtain over the phone from a night watchman the home telephone number of the chief of party of a private charity operating in Bosnia. The ability to ask for directions in Bosnia was crucial since as quickly as road signs were installed, they were taken down to patch leaky roofs of houses damaged during the Balkan War. In one memorable case, hopelessly lost on a gravel road in rural Bosnia (a no-no, since gravel roads were commonly landmined), I stopped, pulled out a Bosnia road map, and asked the only two farmers for miles around, “Gdje jsmo?” (Where are we?) In response one of them pointed at his feet and replied, “Tu!” (Here!)

In Bosnia USDA operated a medium-sized food aid program, eventually totaling $50 million, the monetized proceeds of which were used by private charities to rebuild lives shattered by the war. We focused on using these proceeds for training, microcredit for war widows (whose husbands were generally victims of ethnic cleansing), farmer credit to get food production restarted, and generally restarting the economy. To succeed at this I had to understand the Balkans and the ethnic, cultural, and religious tensions found at a crossroads of three of Samuel Huntington’s civilizations, and thus drew heavily on what I had learned at the UW.

Following a tour of duty in Washington, I returned to Moscow in 2003 as chief of the agriculture section at the U.S. Embassy, with responsibility for Armenia, Belarus and Georgia as well as Russia. The job was at that point much more commercially oriented, with virtually no emphasis on government-to-government assistance, as Russia had rebounded from the 1998 ruble crash and was prospering on $140/barrel oil. Russia was also seeking to accede to the World Trade Organization, and I was immersed in those negotiations, including sessions in Geneva and a “secret” ministerial in London, supposedly as a technical expert on Russian agricultural policy, but often called upon to interpret during critical phases of negotiations and often to translate and analyze complex Russian policy documents. I was also regularly called on to divine Russian negotiating intentions, which given the non-transparent policy environment was a constant challenge.

This was all on top of the routine job of rural travel for crop estimation, which revealed that Russian grain production was rebounding, and led me to predict (to the hoots and laughter of many other analysts at the time) that Russia would shortly emerge as an exporter of wheat, perhaps as much as 20 million metric tons in any given year. When that actually happened two years after my forecast, the laughter faded, and the world grain market was not taken by surprise, thanks to my office’s public reports. I would not have learned what was happening on the ground if I had not been able to converse freely with farmers, rural bankers, grain merchants, and managers of rural cooperatives in their own language. One tactic I used to get past suspicious and sometimes apprehensive Russians was to quote liberally from the works of Il’f and Petrov, particularly “The Golden Calf.” They sensed my love of Russian literature and in particular of Russian satire, and that often helped build a mutual trust. Another fact is that educated Russians tend to use literary allusions in routine conversation (much as English speakers unconsciously quote Shakespeare), so that it is impossible to comprehend what point they are making unless you possess the cultural and literary context.

Toward the end of that tour of duty, on the advice of the Secretary of Agriculture, the President nominated me and the Senate confirmed my promotion to the rank of career minister, the highest rank to which a non-State Department Foreign Service Officer can be promoted. It would not have happened if I hadn’t learned Russian at the UDub.